1891 – 1988

Written by Christopher C. Evans, Grandson

Fort Worth Star-Telegram – December 25, 1984

Thomas Lawrence Brothers of Cresson, Texas

The years of love, Grandpa’s way

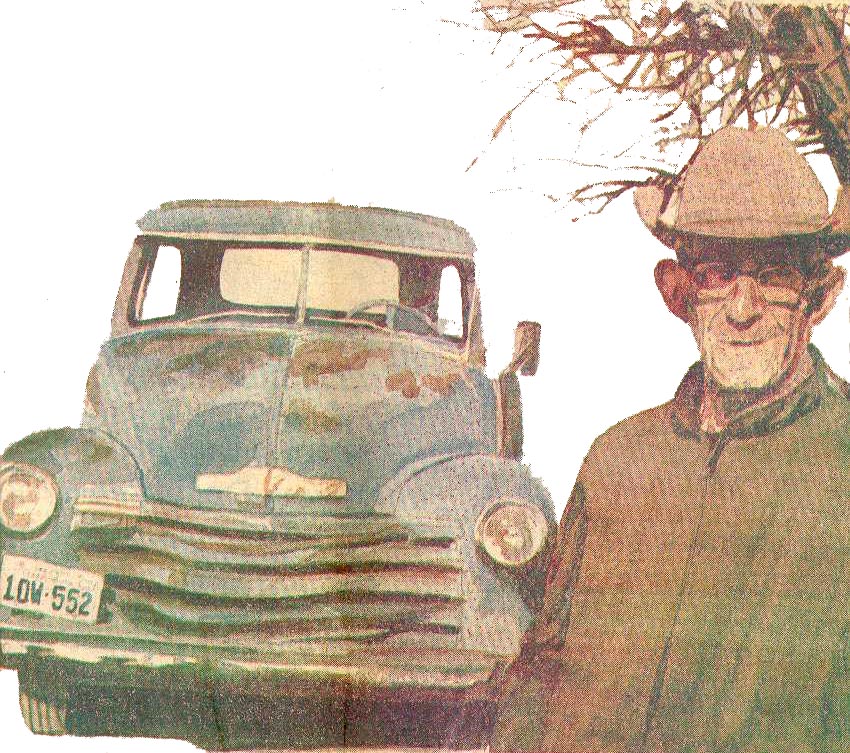

Of cockleburs, windmills and a ’53 pickup that still runs

CRESSON – My earliest memories of him are of an upright middle-aged man when the 1953 GMC pickup was new, in khaki topped by an oily straw hat, with hands that were scarred and bony and blood-tracked. But even then, he was past 60.

Before I was born, Grandpa’s hearing was damaged by countless hours atop a roaring Farmall tractor. Even when I was a tot, Grandpa seemed to slip from time to time into a halcyon trance, sitting there without rocking in a bent-oak rocking chair, drawing softly on a briar pipe stuffed with Prince Albert, with Grandma either at his side or in the kitchen churning cream.

Grandpa the businessman was another animal. In a dark-brown suit, narrow tie and a Peters Brothers Shady Oaks felt hat tilted neatly forward and slightly to one side, he became a city slicker in disguise. He bought new Chrysler Imperials every year or two, just for trips to Fort Worth, Weatherford and Cleburne. He longed to travel, but never found time to do it much, other than the 20-mile junkets into the city for business.

A farmer by calling, Grandpa was something more than a farmer to his grandchildren. He was a cowboy, but only before we were old enough to realize the difference between farmer and cowboy. He did, for a time, keep a broken-down horse and a few cattle. We never thought about the fact that he never wore boots, only lace-up shoes that, once they were too broken in to wear to church, became his workshoes.

On Sundays in church, he’d sing in a high-pitched, off-key falsetto and slip quietly from his pew to collect the offering. When called upon to pray, he did, but in a soft, low monotone that was barely audible. We assumed cowboys sang like that and prayed out loud only reluctantly. We figured it might have had something to do with his past as a Methodist. None of us could say what went on in the Methodist church a block away, but we were sure it couldn’t be good. We were certain that when Grandpa became a Baptist, he left his bad ways, if he had any, behind.

I can see Grandpa now, standing alongside the large rock piles that sit to this day on his farm outside town. More than 60 years he farmed the same land and the rocks never stopped coming. Grandpa worked in the black dirt with mules, then tractors and combines, and he handled a lot of rocks. But never once did I hear him mention the rocks, or for that matter, whether a particular year’s crop was good or bad.

As we grew, we learned a little at a time about this quiet, sinewy man who seemed happiest when he was alone working, tending his windmills or tooling about in his old pickup. What we were told about him rarely came from him directly.

Around Cresson, people talked about how “tight” he was, how he’d drain the oil out of his vehicles, run it through Grandma’s old nylon hose and put it right back in the crankcase. “Too bad he never took time to enjoy life,” a relative told me once. “He’s just a tightwad.”

His grandkids never saw Grandpa that way, although they later learned to appreciate that side of him.

No, our view of him was tainted by the beneficence he showered on us during summers we spent with him and Grandma, when we were privy to his henhouse and his farm, and his pickup once he taught us to drive. He bought us straw hats and fixed our broken bows and, even after we were in college, slipped us $20 bills when we dropped in. For years, we didn’t know why we were special to him, only that we were.

I remember playing on the rocks and in the vacant farmhouse near the barn. And in the barn itself, where vast rooms filled to the top with harvested grain became dry swimming pools when boys climbed the ladder into the rafters and dived headlong into the itch-producing oats.

In that barn, there were rats as big as opossums, easy prey for BB gun-toting boys. Outside, there were rabbits of two varieties, both too swift to be caught on the wrong end of an arrow from a child’s bow.

We chased baby rabbits down on foot, then shoeboxed them back to Cresson where Grandpa had a bottomless chickenwire pen for them in the henhouse. In our big game-hunting days, the pen-an erstwhile chick pen-housed box tortoises and tarantulas, too, but only after summer rains.

Summer nights were filled with fireflies and the raspy lament of katydids, chigger treatments and loamy smelling air that blew incessantly through the windows of Grandpa’s rock house. Summer days were for baseball in a rocky cow pasture adjacent the Cresson School, but Grandpa only tolerated baseball. To him, games were frivolous, extraneous, something to outgrow.

But until he was nearing 90, we didn’t know why his time was so valuable and his manner so terse. It never dawned on us that Grandpa was well past 30 when the Great Depression hit. Only later, when we began to put things together, did we realize he was a product of another time, a time we could never know.

He was born the middle of three siblings Nov. 16, 1891, near the community of Parson’s Station in Parker County. His parents came to Red River County from near Shreveport around 1885. His father, a farmer, was from near Shreveport and his mother, a native Tennessean and a practicing Methodist, arrived in Texas in loaded wagons with a small herd of livestock. Two years later, they moved south and bought a small parcel of farmland four miles south of Anneta in Parker County.

Whatever Parson’s Station was, it isn’t any more, but Grandpa said it was at the Big Bear Creek draw on a natural ridge that the Santa Fe Railroad follows between Cleburne and Weatherford. Whatever life was like there in the 1890s, it wasn’t glamorous. And by 1909, Grandpa-having finished what public rural schools were available as well as a business college-moved to Fort Worth to be storekeeper H.C. Meacham’s office manager. He lasted with Meacham until 1914, when he moved back to Parker County. “I decided I didn’t have no more use for the city,” he once told me.

After two years, Grandpa married a woman whose deceased father had been a prominent rancher in the Cresson area. Grandma, a nurse and a Baptist, was one of five children, three of them boys. After her father died in 1914, Grandma inherited the farm off Texas 171 between Cresson and Godley.

Grandpa took to farming the land, but four years later, two Fort Worth bankers approached him. They said they’d heard of him from his days with Meacham, that they were looking for someone to run a bank at Cresson. Their plan called for using an existing bank building which had been vacated five years earlier.

And from the fall of 1920 until the fall of 1925, Grandpa was vice president and only employee in residence at the First State Bank of Cresson. But the bank, Grandpa told me later, folded “because the population of the Cresson territory was decreasing so fast.”

When the bank closed, Grandpa went back to farming full-time. In 1926, an unforeseen thing happened.

Grandma, because of a childhood illness, was barren. Before she wed, she had told Grandpa they would never have children. But shortly before Christmas 1926, Grandma came home from her nursing duties with a 2 1/2-pound child that had been given up for dead. The child’s mother had died during childbirth.

At first, Grandpa was reluctant about taking a child who might not live. Grandma, ever the nurse, won him over. She said if the child had any chance at all, it was in her care. Grandpa later told me that when he first picked the baby up, “she’d fit in my hand.”

The baby lived, and whether she ever was formally adopted, I cannot be sure. But she assumed Grandpa’s last name.

When the child was 12, Grandpa built his dream house, not on the farm but in Cresson proper. He carted ruddy sandstone from Millsap in Parker County and ordered wooden shingles from a company out of state. He’d never built a house, but he started construction in March 1938 and finished in August.

For almost a decade, Grandpa and Grandma lived in the house. They watched their adopted daughter go off to college and fall in love with a well-heeled military man.

And on June 7, 1946, the well-liked military man came to call. He asked Grandpa for permission to take the daughter flying. The two of them would drive to Weatherford, where the military man would rent a BT-13 training aircraft. For fun, they promised to buzz Grandpa’s farm.

Some time later, as Grandpa was cutting grass on his tractor, he watched the plane come into view then dip and crash headlong into the earth on his own farm.

He sent his only hired hand to call for an ambulance, then rushed to the remains of the plane. He pulled the military man, who was dead, from the wreckage. After an ambulance arrived, he worked with rescuers to extricate his daughter from the gnarled metal. Then he followed the ambulance to Fort Worth, arriving at the hospital “soaked with blood,” according to an eyewitness.

The daughter, her back broken in more than a dozen places, lay unconscious for several days, then recovered. After she spent almost a year in a brace, doctors told her she would never bear a child. She married a minister and had three children.

The children-Grandpa’s grandchildren-eventually grew up and moved away, but not until Grandpa’s impression was indelibly etched in their minds. We saw him each Christmas, sometimes more often that that, but it was at Christmas during his later years that we began to wonder what Grandpa was thinking about us, about the world around him.

His deafness became more of a problem and, when the house would fill with family, he seemed to drift off more and take more trips to “the pasture”-or the Cresson Cemetery nearby, where Grandma is buried-to be alone. When he stayed at home with family around, he commonly fell asleep in his rocker, allowing his pipe to droop from the corner of his mouth, then fall into his lap.

When Grandma died, we feared Grandpa wouldn’t be around much longer. He insisted on living alone and cooking for himself. He stopped buying Imperial automobiles for trips to the city and settled for cheaper Chrysler models, but drove them very little. When he did drive, we worried. But he still seemed to find respite by slipping off to the farm or the henhouse to be alone.

Though the pasture still was leased, it lay fallow more and more, but he continued his regimen, battling cockleburs with a sling and making at least two trips a day to the farm to monitor his windmills. For a time, Russian thistles were a problem, but he refused to pay anyone to exterminate them, choosing the smooth-handled sling over the expense of commercial chemical warfare.

The old house looks almost like new today, the grout between the rocks still resplendent in its rich yellow cast. The roof leaks and stains the ornate wallpaper on the ceilings with inverted puddles. There’s nary an air conditioner on the premises; Grandpa bought one 20 years ago and sold it the next year. Too cold and too costly, he always said.

The old rock bank, a long, one-room structure that sat near the intersection of Texas 177 and U.S. 377, met the wrecking ball earlier this month.

The farm has a weary look about it, but the smells and sounds are much the same as they were when we were kids. The gates are sagging and rabbits are scarce.

And late this afternoon, after all packages have been opened and the family Christmas gathering has broken up, there will come a tremendous, unmuffled roar from inside Grandpa’s rock garage.

The ’53 GMC suddenly will slowly emerge from the garage and, in its own time, wobble sidelong down Texas 171, wheezing from scores of gallons of “recycled” motor oil that have passed through it only after having been passed through Grandma’s old nylon hose beforehand.

The radio, which only crackles, will be on, but it won’t be audible because of the roar of the truck’s engine and the old tools bouncing around in back. The driver will have an unlit pipe lodged tautly between his teeth, a grease-stained hat on his head and a placid, faraway look in his eyes.

Grandpa will be making his rounds.